OUR BODIES TURNED INTO WEAPONS

Our movement, while taking care of its wounds, kept taking steps against fascism based on revolutionary violence. After the ANAP-government took power, our movement wage a propaganda battle against the government, showing its fascist face. Besides applying classic propaganda, 10 city offices of the ANAP in Istanbul were destroyed by bombs in this battle. In the Turkey of those days, in which it was quiet, such actions – actions which drew all the government’s violence on them – were quite sensational. However, stability was lacking and the actions were not increased or accelerated, They weren’t on the daily agenda and therefore they remained temporary impressions.

The psychological superiority of the junta continued. The resistance inside the prisons ensured their speciality of being opposition centres. Besides the battle for the prisoners’ honour and identity, we had to connect the potential of resistance and the prisoners’ strength with the political struggle which influences the people’s masses, giving them morale support and countering the pacification tactics of the junta.

After September 12, many groups put the “tactical retreat” on their agenda. Influenced by the junta’s psychology, they began to drift, deviating to the right, and they went into exile. Since their appearance on the political stage, they had not really thought about fascism, the state, strategy, tactics or struggle. The coup of September 12, 1980, confused them and they lost their strength. Ignorant of their land and the revolution, they theorised about imperialism and had the bourgeois ideology forced on themselves which started to determine their direction in one way or the other. From this notion, opportunism thought it could not remain on its feet although the weakness of the junta was apparent to the public abroad and in the country despite its illusory strength. Opportunism exaggerated the strength of the junta as “invincible” and the struggle against it was seen as “in vain”. A line of “anti-resistance” was pursued inside the prisons, a line of “passive acceptance”, and it was tried to legitimise this line.

This attitude of capitulation especially became apparent in the TKP (Turkish Communist Party) and Aydinlik which was at their side. Many other left groups drifted between the line of resistance and the capitulation line of the TKP. When we look at the attitude of Devrimci Yol in the Mamak prison – many of the prisoners in Mamak were supporters of Devrimci Yol, the cadres of their central organ and other leading cadres were imprisoned there -, Devrimci Yol is responsible for the fact that Mamak turned into a rehabilitation centre for the junta. The junta played cat and mouse with the prisoners in Mamak. The second rehabilitation centre for the junta was to be the prison of Diyarbakir where the majority of the prisoners were Kurdish nationalists. The junta drew its lessons from these centres and attacked the other prisons in the hope to achieve the same results. The prisoners in Mamak and Diyarbakir were unable to prevent the successes of the junta. The most important success was that the junta was able to show the people in Turkey and abroad that revolutionaries from Turkey and Kurdistan were surrendering and repenting. The people’s masses were negatively influenced by this skilfully worked out propaganda. This went so far that Mamak and Diyarbakir become institutions of intimidation and pacification of the people’s masses.

The junta, from the first day after taking over power, intended to attack the prisons intensively to force the prisoners to capitulate before they were able to recover from the confusion. This plan was put into action. Fundamental to this image of capitulation, confusion and deprivation was an insufficient and non-revolutionary analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of the junta and the period prior to September 12 as well, of the dead ends of overt fascism and of the power of a revolutionary movement, based on its own strength. The first attacks of the junta caused a panic. The junta was seen as almighty because of the fear for massacres which would be even worse than the ones which were already committed. In the name of preventing even bigger acts of capitulation, the own activities were step by step adapted to capitulation. The demands of the junta were accepted one by one. Every act of acceptance led to a new attack and after every attack followed acceptance of yet again another demand. In a short time, the junta succeeded in subjecting the prisoners in Mamak and Diyarbakir with this tactic. This submission was used against the people with a successful propaganda. The most urgent task of the revolutionaries was to prevent this propaganda, to show that the revolutionaries were not surrendering. It was inevitable that there were going to be martyrs to achieve this goal, to prevent this policy of submission, to influence the left and the people accordingly.

Our determined and radical line of resistance was successfully applied until the elections of 1983, despite attempts by the entire left to retreat, despite the crushing of all kinds of resistance. The line of resistance inside the prisons, together with the refusal to confess in court, influenced almost all, from the left to the petite-bourgeois intellectuals. Opportunism had not internalised the revolutionary consciousness and the reality in our country. They even opposed the struggle for defending the most basic rights, stating that the junta was very strong in it first years and that they would not compromise. But when the junta put elections on the agenda in 1983, they believed in a return to democracy and they were misled by the dream that the junta would soften its pressure and the terror against the prisoners, that it would stop altogether in the end. Consequently, they argued – together with the demagogues – that it was useless to take a stand inside the prisons, that it was the task of those outside to take a political stand. They stated that the prisons were no centres of struggle. Where there was no ideological stability, deviation to the right or to the left was inevitable.

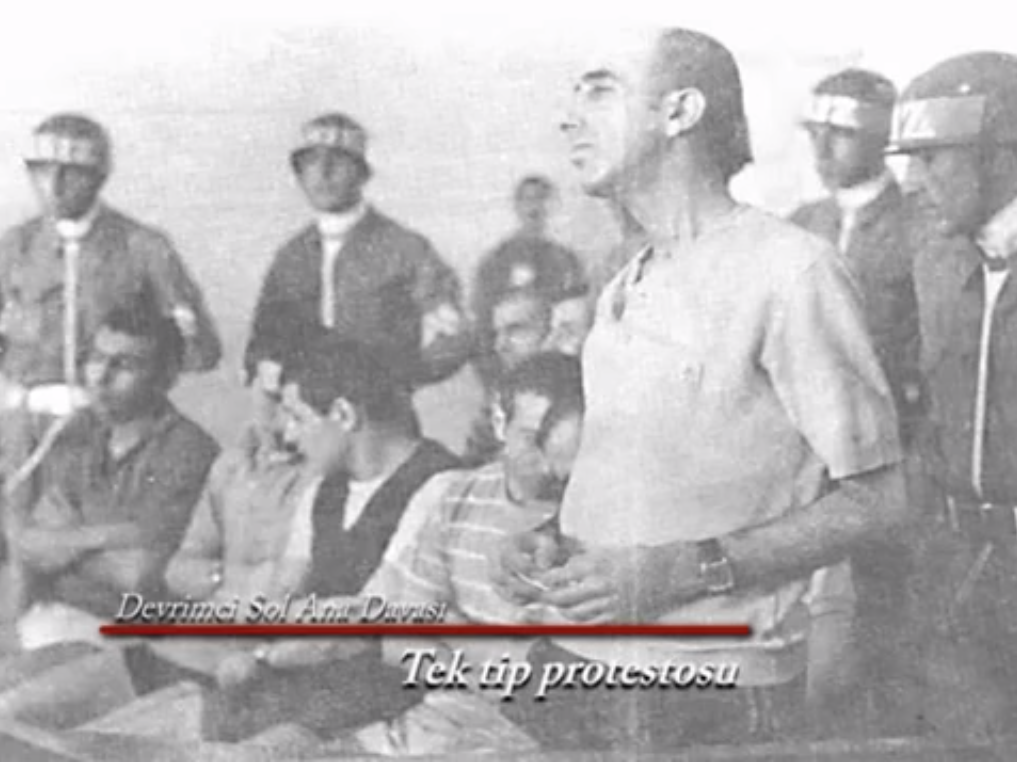

While opportunism was fantasising, the junta presented the obliged prison uniforms as if it had read the mind of the opportunists. These went through even more confusion. While expecting democracy, an even worse attack occurred. While the junta completed its transition program, away from overt fascism, it did not let go of its program of rehabilitating the prisoners. Would those who didn’t understand that fascism is Turkey was trying to behind a democracy game, would they be able to recognise the reality of fascism after painful experiences? The fantasies of the opportunists were not just characteristic for the prisons. It even went so far that some movements, like the Kurtulus who escaped the country even before the coup of September 12, yelling “the junta is coming”, returned to the country to organise again, believing there would be a return to democracy after the elections of 1983. The situation they found had been unexpected. Their dreams had been very big. All the left organisations were either imprisoned, or they had ceased to exist. Nothing was moving in the country. They had developed big tactics, they had retreated, their strength had not been destroyed, so they believed. They were going to storm the country with their forces, they were going to attract the entire revolutionary potential. Thinking of all kinds of hindrances, they did not neglect their ideological attacks against our movement. It’s sad, but when these people, who had never been entrenched in the soil of the country, who were estranged from the people, who were unable to free themselves from abstract and complex thoughts, from the lability of petite-bourgeois intellectuals, who cultivated discouragement and disbelieve, who even imported some right-wing ideas from Europe, when these people returned they had only a couple of months to live. Kurtulus, happily yelling “All the others collapsed, we are the only ones who came out unharmed”, even before they returned to the country, some months later – after hitting their heads against the prison walls and regaining consciousness (did they really?) – stated: “All of us have been hit, we received our share as well.” Will they ever learn?

The years of defeat were the environment in which all kinds of ideological perversity, degeneration, immorality, split from the people, self-denial and philosophical idealism grew. This reality was the result of the attacks and the submission policy of the bourgeoisie. To maintain the existence of our organisation, not losing the soil under our feet, to be able to lead our people, we had to fight all kinds of opportunistic tendencies which attacked our ideological clarity, threatening our stability, supporting the oligarchy and feeding the morale of defeat. We had to act against all the tendencies who took over the ideology of opportunism voluntarily, who wanted to destroy us, leading us step by step into decay, trying to make us dependent on the system, institutionalising the status quo. We couldn’t allow influence by the bourgeoisie in different forms and disguises, from the inside and outside, an influence in a right-wing, a left-wing, revisionist and compromising manner. We had to draw a clear line. With such an attitude, peculiarities didn’t count much and we couldn’t allow much room for doubt. The existence of our organisation depended on our ability to overcome this process ideologically stable. Whether or not we had a future, depended on this question. Our line of resistance and our ways of struggle under the conditions of imprisonment were the means to fight against our internal and external enemies at the same time, rendering them ineffective. This notion and this perspective developed self-confidence of our cadres and sympathisers and it enabled us to continue the resistance for years, based on our own strength and despite all the differing views. We were able to achieve positive results.

Opportunism, in tow of democracy against the obligation of prison uniforms, couldn’t cope with the resistance which required long-term sacrifices. Opportunism got stuck in a certain position and it was tired and exhausted. While they cultivated this attitude, dreaming of a new democracy, it showed its weakness against the new wave of attacks, again stating that the junta was all-powerful. At first they thought the junta would drop its demand after a short general resistance. The enemy and the left had to go through a test of determination. The most determined would win. The way of thinking and the psychology of opportunism didn’t allow them to emerge victorious. At the end, more than one thousand prisoners participated in the general resistance of 1983 which turned into a war of will power between the enemy and the left. At the moment the resistance reached it summit, when the prisoners were supported by the revolutionary and democratic forces in the country and the world, when this democracy game of the junta was exposed, when the junta was in a difficult position, forced to compromise, at that moment opportunism began to doubt even more and they broke off the resistance, thus enabling the junta an easy victory. The news agencies of the world reported: “The junta succeeded in breaking the resistance by inciting the prisoners against each other”. The enemy was able to step up its program of rehabilitation. Opportunism had erred once again when it assumed breaking off the resistance would lead to a compromise with the enemy. The enemy then destroyed the hopes of opportunism – which weren’t much anyway – by increasing the attacks as soon as the resistance was ended. The fools were unable to learn from experience. Opportunism no longer had the strength to organise a new resistance. It went through a major moral destruction. Words like “We will resist, we will not accept the prison uniforms” were just words which they didn’t believe themselves. Opportunism, forced by us to resist, began to legitimise their retreat. The tactic of retreat had always been present in prison, but until that time it did not have a real chance. Now the prisoners, who pursued the same ideology which was discovered by the left abroad with the coup of September 12, could test their theory after a delay of three or four years. They made quite an effort to convince themselves and their sympathisers. In the name of a tactical retreat, many historical examples like Brest-Litovsk and the NEP were linked with the conditions in prison and used as an argument to convince. In fact it was quite clear what they were discussing and wanted. In stead of saying “We don’t have the strength to resist anymore, we have to accept the prison uniforms”, they felt the need for a theoretical disguise, even though this reached the level of absurdity. With the retreat of opportunism, it became obvious that the sacrifices of those who resisted in the prisons of Istanbul would be bigger than when a general resistance had been achieved. We had to be prepared to give these sacrifices.

We couldn’t give the enemy the present of a subjecting human type which they wanted to create to present to the people after forcing the prisoners in all prisons to wear prison uniforms. We wanted to prevent an attitude which would increase the disappointment among the people’s masses, caused by Mamak and Diyarbakir, giving the junta new propaganda material. We had to sent the people the message “We didn’t surrender despite all the attacks of the enemy” with our loudest voice and under objective conditions.

It was obvious that the retreat by opportunism from the position of resistance against the prison uniforms would lead to a massive decline of the participation. We had to compensate this loss. If need be totally on our own, depending on our own strength, we had to erect a barricade against the wave of attacks of the oligarchy, we had to prevent submission, even if there were going to be martyrs. The oligarchy made good use of the emotional situation of opportunism after they broke off the general hungerstrike of 1983. The intention of the opportunists to wear the prison uniforms increased the hopes of fascism and they started to demonstrate their determination. But despite these demonstrations of strength, despite the elections of 1983 and despite other democracy manoeuvres, fascism went through a deep economical and political crisis in the country and they were confronted with isolation abroad. We were able to stop the wave of subjugation by looking at the dead ends of the junta and establishing a determined resistance which was not afraid of sacrifices. In different ways we were able to play a positive role inside and outside of the prisons, giving the spirit of resistance a new dynamic. The abolition of the prison uniforms and other means of submission would mean the failure of the fascist policy of the junta against the prisoners. We would enter a phase in which the pressure of fascism to subjugate the prisoners would decrease and in which a part of their rights would be recognised. Achieving these targets would depend on our determination to resist and our revolutionary policy. Our cadres and sympathisers were prepared to accept this historical task. They had gone through this process from the beginning, they had seen the difference between our policy and that of opportunism and they stood up against the policy of deviating to the right. These were the circumstances in which the hungerstrike till death came on the agenda. When no other left group except the TIKB accepted a new general resistance or a hungerstrike till death, the hungerstrike till death was started with the TIKB. In the context of an organised resistance on all levels of the masses and the cadres, the hungerstrike till death volunteers entered the phase of their death fast on April 13, 1983. The oligarchy, still determined, launched their attack on the first day of the hungerstrike till death. This resistance, which would last 75 days, was almost daily under physical, psychological and ideological attack. During the resistance, which would demand martyrs as well, and while the oligarchy continued its attacks against the resisting prisoners, the opportunists discussed the prison uniforms, made use of the better conditions (as a result of the resistance) and joined the oligarchy in their attack with gossip and speculations, as if nothing was happening. They could not wait for the resistance to end in defeat.

Although we gave leading comrades like ABDULLAH MERAL and HAYDAR BASBAG, our cadre HASAN TELCI and M. FATIH ÖKTÜLMÜS, one of the leaders of the TIKB, as a sacrifice, the abolition of the prison uniform could not be achieved directly. But the resistance, making the issue of the prison uniforms known to the world public opinion, claiming four martyrs, became a barricade against the oppression policy of the junta against the prisoners. It sent a message to the people’s masses that the revolutionaries would never surrender – even if it would cost them their lives – and it prevented the junta from misleading the consciousness of the masses. And history was to write about the resistance of the prisoners from Devrimci Sol: “They died, but they never surrendered.”

The importance of this resistance inside and outside the prisons could not be grasped entirely by the masses under the conditions of those days. But in time they would understand it more clearly and grasp the different aspects.

In the mean time, this resistance was a process in which almost everybody in our ranks, from the masses, the cadres and the leadership, would be tested once again and our ideological stability was tried.

Maybe this resistance did not achieve a lot considering concrete rights. But that had not been the essential goal, it was about the political gain. And in that field it was a victory. The crown of this victory was the continuance of the resistance in which we developed new ways of resistance, building on the political gain. We would not accept the prison uniforms, we would not follow any order, and we would continue the resistance.

By wearing the prison uniforms by the opportunists, for the first time in the history of the prisons since September 12, 1980, a clear division became visible. The opportunistic view was caringly packed in demagogic arguments like Brest-Litovsk, the NEP and the individualistic aspects of human beings. In that phase, opportunism stated: “The junta does not want to force us to wear the prison uniforms”. This went into the history of the prisons as a negative example. While we now think of it with a sad smile, they presented wearing the prison uniforms as a victory. Opportunism thought it would get a rest by accepting to wear the prison uniforms, it would be freed from the junta’s pressure. However, the junta – being handed this big concession – continued the pressure to gain even more. Opportunism plunged into confusion again. Because of our refusal to wear prison uniforms, they denied us and the prisoners of the TKIB all the rights, even the right to witness our own trials. But we did not wear the “blue coffins” and brought freedom within imprisonment to life. Within the prisons, we were separated from all the others. Our refusal to accept the prison uniforms caused the attacks not to be aimed against those who wore them. Attacks against them could have led to loosing the successes gained from the opportunists. For this reason the junta tried, while charming opportunism, to maintain their position considering the prison uniforms with a policy of “divide and rule”.

It was very difficult for the junta to explain the situation of the prisoners – who for two years already weren’t allowed to witness their own trials because they refused the prison uniforms – to world public opinion. At that time, the organisation of our relatives developed and they became the voice which carried the resistance of the prisoners to the outside. The junta, obliged to maintain its democracy game, could no longer continue their attacks. We had to continue our resistance. At November 15, 1985, the junta began to give in to our resistance. Forcing all our rights from the junta, we completely abolished the prison uniforms in January 1986, thus causing a major defeat for the junta on the prisons’ front. The historical mission of our resistance had become reality. Now the independents, as well as the opportunists, could take off their blue coffins. We gave four martyrs in writing this chapter of history.

Our ideological stability and our organisatorial determination have many sides. They should not be limited to the prisons’ front, they should be seen as a process, full of political lessons which, very important even today, lessons we still base ourselves on.

Abroad, the traitor Pasa had severed almost all relations with our country, taking care of his own personal life. In our country itself there had been more arrests and Sabo was now on her own and this was not enough. There was a strong need for new activists. Our resistance of the hungerstrike till death had caused a strong sympathy among our cadres, sympathisers and the revolutionary potential in general. However, our organisation was to weak to gather this sympathy. Our rural guerrilla unit of the Black Sea, not giving evidence of its fighting existence on September 12, had given its commander Necdet Pismisler and many other comrades as martyrs during battles with the enemy in 1981.

Also in 1981, the rural guerrilla unit in Sivas-Tokat was taken prisoner. The rural guerrilla unit in Dersim succeeded to survive till the end of 1984, conducting a few actions on a lower level because they had chosen self-preservation as its highest principle, not starting any serious action even though they were the most experienced unit, operating in an area where the revolutionary potential was concentrated. When they were arrested as well, at the end of 1984, our guerrilla activity ended there as well.

Retreat was a necessity.

Fortunately, M.A. was released in that time. After September 12, he had taken over some tasks in the Central Committee. After discussing our duties and problems outside the prison, he was sent away with a high morale. We thought the organisation would soon go ahead because we now had another leader on the outside we trusted, besides Sabo. However, M.A. used this trust for his own personal problems and, although a couple of months went by, he did not take over any duties.

He decided where meetings should take place, but seldom showed up himself, and he risked the lives of our best people. He postponed his duties with excuses like health and family problems. Months later he came up with the excuse to see “nightmares”. M.A. was now on the road to treason. After he was busy with his nightmares for a while, he stated to be afraid and his life as a revolutionary was ended. In all these years, this was a line which was pursued by people who do not want to lead a revolutionary life. These people have to proof to the police, their environment and all others that they are not engaged in revolutionary activities anymore. Therefore this road leads to loss of character and honour. The police controls them and watches them to know what they are doing. When the police discovers they do not want to be revolutionaries anymore, they are contacted and forced, pressurised, to at least spy for them. This is how the police contacted M.A. He humiliated himself so much, he had drinks and dinner with those who had tortured him. Even though he did not become a spy, he promised them never to be a revolutionary anymore.

The years of defeat were difficult years, and years of betrayal. Despite this betrayal, we continued our road. As a prisoner, is it easier in a certain way to resist the pressure and torture by the enemy. Because it is evident who the enemy is. But the pain, caused by the traitors who went against their own values, was much bigger. On the other hand this treason worked like a whip, strengthening our will to be free, intensifying our efforts to get out.

The prisons have always had two faces. At one side, they are like schools. At the other, they are grinding people like a millstone, especially when the organisations lost strength on the outside and the enemy is psychologically superior. As long as the lives of the people are not in danger and people are not overburdened, a collective life and collective resistance by the people can be maintained on the line of resistance. But when there is no split between revolution and contra-revolution, when there is no separation from the system, returning to the system will not be difficult. People who went through torture and imprisonment and get on the other side of the walls will be confronted there with this torture, this pressure and the difficulties of imprisonment by the oligarchy again in order to break their revolutionary identity.

Being a revolutionary means being prepared for such things. When the struggle intensifies, the contra-revolution will increase its violence. Death is a real possibility in this struggle. Immediately people are forced to choose between the system and the revolution. An undetermined, waving personality – who has not freed himself really from the system – is confronted with the expectations of his comrades and the people on the one hand, and the threats of the oligarchy with torture, terror and death on the other. Those who do not believe in the superiority of the revolution, those who are light-weight, will give in to the pressure and the violence of the enemy, and they will re-integrate in the system. They will abandon their people and comrades and betray them. This kind of personality is petite-bourgeois, weak and not prepared to sacrifice, living on the expectation of a soon to come revolution. They are the most radical ones in times of victory, they crouch for the enemy in the phases of defeat, always at the edge of treason. They carry the potential of betrayal into the revolution…

Our comrade Niyazi was released in October 1985. Since 1970, he had gone through almost all levels of development of our movement, willing to sacrifice. Niyazi still had memories of the struggle which were unknown to the enemy and many other, knowledge which had not been revealed till then. Under all circumstances, he had justified the trust we had in him, after September 12, he took over political responsibility in the Central Committee and we could entrust him many things without hesitation. Comrade Niyazi was no M.A. Neither in the past, nor in prison, had M.A. disassociated himself from the system. But comrade Niyazi was different. He spent his childhood in poverty, and as a small child he had to earn his own living, growing up in the poorest neighbourhoods of the people. Except for his intellectual personality, he never had any bonds with the system, disassociating himself from it in an early stage. He was one of the leaders of our movement. We had no doubts that his freedom was of great importance to our movement. We were full of confidence, our morale was high. We felt as if not only Niyazi, but all of us, hundreds of prisoners were being released. He would carry our ideals and feelings, our fighting spirit, our anger and fury to the outside. This was the atmosphere when we sent Niyazi to the outside.

Huge problems were awaiting him. The tasks he was confronted with were enormous. He had to re-develop the organisation, deal with the treason abroad, find a new form for the movement, build up a central structure and increase the struggle. It was impossible to increase the struggle, to determine the agenda, with the existing organisation, the existing network of relations and the remaining resources. Overt fascism, despite it continuance, was in a phase of renovation. Therefore it was fruitless to insist on spreading the resistance by means of the existing strength and structure. We would only loose even more strength. To gain strength and prepare for a phase of expansion, we had to end the discussions about a tactical retreat which started at the end of 1984. Niyazi soon escaped from police surveillance and he began to fulfil his tasks. Now Niyazi and Sabo were leading our movement.

The situation of the movement was evaluated in detail and discussed with the most responsible cadres. A tactical retreat was decided. This tactical retreat was not meant to be a phase of complete passivity. Without losing strength, there were to be propaganda activities and actions from time to time. But this phase was primarily meant to gain form, gather strength, stabilise ourselves, and speeding up the phase of becoming a party.

It was announced that the traitor P.G., with whom all contacts were broken off, who had transformed our organisation abroad into a mess for his own benefits, would be held accountable. All his efforts to split our movement abroad were exposed and he was isolated himself. He and his wife, controlled by the French police, began to deal with the Mafia when he understood he could not abuse the revolutionary movement and the masses for his own family and acquaintances. The cadres and sympathisers of our movement felt a great anger against this traitor who abandoned us when we were under enemy fire. We would never forgive him.

Even though we were not well established, we intervened abroad and initiated steps to clean up the situation. Contacts, limited and distorted in possibilities, were slowly restored and expanded.

The ANAP-government had to implement some democratic reforms, albeit in a restricted form. The silence of the masses, enforced by pressure and terror, began to break among some segments of the people. Several classes and segments, relatives of the prisoners, youngsters, students, the workers, even some bourgeois parties began – albeit in a reformist way – to raise their voices and they demanded their rights. We had to be the voice which expressed the demands of the people, silenced by the junta through pressure and bans. We had to take the struggle of the masses in our hands, together with the struggle of our movement. Without creating a base for a mass potential, a broad and stable cadre organisation is impossible. We had to lead the masses in their attempt to stand up again with their economic and democratic demands, without falling in the trap of legality. We had to take courageous decisions in the ideology, policy and organisation of the masses. We had to implement them, we had to strengthen our underground organisation more and more each day, without getting exposed.

While analysing all the possibilities, we had to become active soon in a radical way. We were neither an organisation which viewed fascism as invincible, nor were we day dreaming of elections and democracy. After well evaluating the strength of the masses and those of the powers that be, we were able to take some successful steps and in a short while we expanded our leadership of the mass movement, we expanded the cadre education and in doing so we were able to leave the phase of tactical retreat behind ourselves. Besides this, we pursued high aims like setting up military training facilities to obtain a more professional urban and rural guerrilla, and setting up a rear front for the urban and rural guerrilla.

In order to give direction to the mass movement, to prevent defeats and build a barricade against the world-wide storm of opportunism, to develop our ideological unity, it was a absolutely necessary task to publish a legal and periodic press organ to reach the masses. Furthermore, we needed all kinds of democratic organisations to gather the masses and to become their mouth-piece. The relatives of the prisoners had mobilised a part of the masses’ strength. We had to gather this strength within the democratic organisations to increase its effect. To gather the relatives in one democratic platform for the first time in the history of Turkey, we addressed all political movements and even some individuals. There was no reaction to our appeal from the entire opportunistic and reformist left In stead they cunningly got together themselves to create a democratic organisation of the same kind. Although this creation occurred in a hostile fashion, it is useful nevertheless. So two different organisations appeared on the same field. The tradition was not ended. Almost all the opportunistic and reformist had come together. Even those who had denounced each other as “Maoist Grey Wolves”, “lackeys of the Russians”, “Goschists” and “contra-revolutionary traitors”. Without a single word of self-criticism, to came together, “ripened”. Even the TIKB, which participated in the hungerstrike till death together with us, in which the prisoners and their families showed an example of solidarity, seemingly did not see its future at our side because they did not forget to take their place at the side of the opportunists and reformists.